|

Fantasy worlds are where dreams come true, especially when it comes to Disney-style fairy tales. Sleeping Beauty, for example, is a princess expecting a handsome prince to rescue her, and that’s exactly what happens. In the end everybody gets what they wanted all along. That was 1950s Disney. But then in 2001 DreamWorks Animation came along with their little film Shrek and shattered what we think of as the traditional fairy tale.

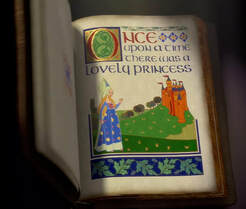

Inspired by the picture book by William Steig, the film Shrek starts with the reading of a story about a princess locked in a tower being guarded by a ferocious dragon, awaiting true love’s first kiss. At that moment Shrek laughs and says, “Like that’s ever going to happen!” He rips off a page from the storybook and presumably uses it as toilet paper. You’d be hard-pressed to come up with a more irreverent opening if you tried. And with that, Walt Disney’s work gets flushed down the drain.

Over and over the film reminds us of our fairy tale expectations, only to dash them to pieces in front of our eyes. We watch as Geppetto sells Pinocchio for “twenty pieces of silver” and Peter Pan betrays Tinkerbell. Lord Farquaad wants to marry a princess, not out of love but to make himself king. When the Magic Mirror runs through three eligible candidates, describing Cinderella as “a mentally abused shut-in,” Farquaad can’t decide on which lucky lady to make his bride and seems to choose Fiona only by random selection. Being too cowardly to free her himself, Farquaad sends off Shrek the ogre to do his dirty work.

The princess Fiona bears the brunt of the filmmakers’ iconoclastic quest. We’ve told stories like hers for ages. In Greek mythology, for instance, the hero Perseus saves the princess Andromeda from a terrifying sea monster. So you can hardly blame Fiona for expecting a dashing prince to ride up out of the morning mist on his magnificent steed. But instead, who should show up but “some ogre and his pet.” Instead of kissing her, Shrek gives her a good shake and tells her to “Wake up!” When Fiona offers him her handkerchief as a token of her love, Shrek uses it to wipe dirt off his face and then hands it right back to her. After he removes his helmet Fiona realizes that Shrek is an ogre and refuses to accompany this “unorthodox” rescuer back to the castle. So Shrek picks her up and literally carries her kicking and screaming. Not a great beginning for what we've been told should have been a budding romance.

Why do we seem to gravitate to parody in today’s society? Is it because of our cynicism, because we don’t believe in true love, or living happily ever after? That’s not reality, we say. That’s fantasy. Now, I’ve talked before about how we use the word fantasy. In everyday conversation it’s common to use the word to dismiss something as totally impossible or unrealistic. Those who believe in fantasy are naïve and gullible. If you lived under Lord Farquaad’s rule and believed him to be the wise and benevolent leader he pretends to be, you might just trust in his vision for making the land of Duloc “a perfect place.” And you might one day find yourself selling out your fairy tale friends.

Shrek the ogre is totally content in his cynicism. Or at least he starts out that way. He doesn’t trust kings in castles or believe in happily-ever-after endings. Or fairy tale princesses for that matter. When Donkey mentions the “fire-breathing pain-in-the-neck” they’re going to encounter on their journey, Shrek misses the fact that Donkey is talking about the dragon and assumes he’s talking about the princess. Being an ogre has taught him not to expect much from others. He knows that people are more likely to come at him with torches and pitchforks than a hand of friendship. Shrek’s imagination doesn’t extend very far beyond the borders of his property. As Shrek tells Donkey in an untimely outburst, “I live alone! My swamp! Me! Nobody else! Understand? Nobody! Especially useless, pathetic, annoying, talking donkeys!” Shrek totally misses out on the opportunity to share his life with others, something he thinks is just too good to be true.

All Shrek wants is what’s rightfully his. He wants to live undisturbed in his swamp like he always has. That’s why he goes on his quest to retrieve the princess after all, so that Lord Farquaad will finally leave his home alone. And yet when Shrek does get back to his swamp, when he gets everything he thought he wanted and he’s sitting alone at dinner eating a handful of delicious slugs and grubs, he realizes that something’s missing, or rather, someone. But of course the idea’s ridiculous. A princess falling in love with an ogre? That’s not reality. That’s fantasy.

But I would object to using the word fantasy as a pejorative. Fantasy stories do not stand in opposition to everything we know to be true. Rather, they shine a light on truth we may have forgotten. Fantasy reveals that there's more to the story than we know. When it feels like you’re being crushed by a mundane, banal, power-seeking ruler, there’s still a chance that a sprinkling of magic can turn the tables. Even a controlling ruler like Farquaad does not take every probability into account. He never suspects that perhaps Fiona, living alone as an outcast all those years and being transformed every night into a green-faced ogre, might find some sympathy with Shrek. He never suspects that she might understand Shrek, let alone love him.

And as it turns out, Fiona does love him. She loves him like no other person could. It’s almost like they were meant for each other, in a fairy tale kind of way. Rather than amounting to a cynical parody, the film praises the genuine bond between Shrek and Fiona. And it shows us that good fantasy makes room for the possibility that there is something more, some element baked into the story from the very beginning, the real impact of which is only revealed at the end. Suddenly everything makes sense and the impossible becomes reality before our eyes. We’re no strangers to this concept in our world. We know that the impossible happens all the time, whether it’s the eradication of infectious diseases or the rescue of 338,000 Allied soldiers from Dunkirk during World War II. Fantasy allows for things we never could have dreamed of. It allows for the miraculous—and so should we.

Comments

|

David Raphael HilderJoin the conversation as we explore the best there is in fantasy, sci-fi, adventure, and of course, the classics Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|