|

What makes life worth living? What do you need in order to live a fulfilling life? How we answer these questions will reveal what we believe is most important. If we asked the pirate Jack Sparrow, I can guess what he’d say. Freedom. A ship of his own and the never-ending horizon before him, a world of possibilities. And, of course, a bottle of rum thrown in.

We pursue the things we value. Our priorities act as our compass, to use a seafaring metaphor, guiding us to what we truly desire. The 2003 film Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl introduces a cast of cut-throat villains and imperfect heroes, all of whom are pursuing something. Whatever questionable actions they engage in can all be explained by taking a look at their deeper motivations. On the surface, it’s a fun, swashbuckling story. The soundtrack alone is enough to make you feel like an adventurer. A lot of the film’s charm comes from the quirky Jack Sparrow, the loveable pirate with that mischievous glint in his eye. You can’t help but root for him. Sure, he’s a pirate, but he’s one of the good ones. The movie does a lot to make those who engage in piracy more sympathetic.

Comments

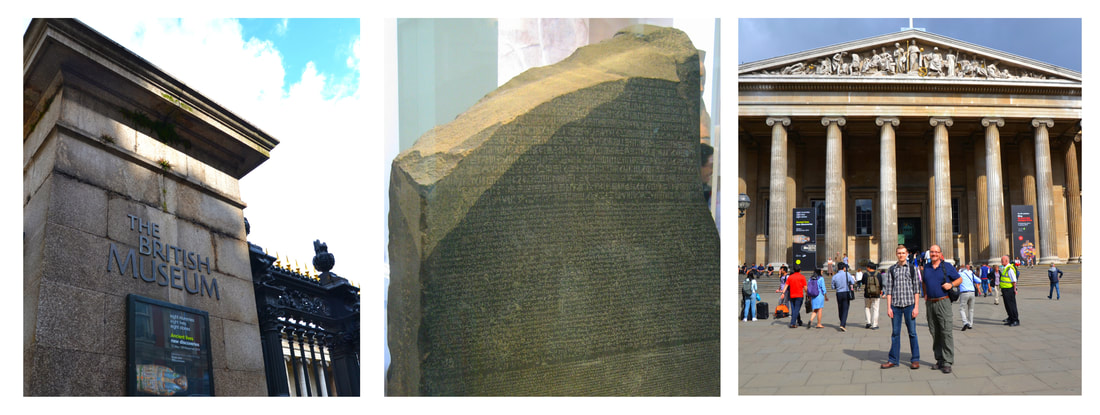

The Rosetta Stone holds the key to understanding the ancient past. It's a hefty, grey slab from 2,200 years ago, engraved with three languages—hieroglyphs, Demotic Egyptian, and Ancient Greek. I was able to see the stone in London in 2014. As one of the most popular artifacts at the British Museum, naturally it was surrounded by crowds of excited tourists taking photos. We were all craning our necks to catch a glimpse of this seemingly uninteresting rock. Out of all the museum's artifacts, like colourful Roman and Greek mosaics (which are great by the way), towering Babylonian statues of winged bulls crowned with human heads, and sunken treasures of the Vikings, you have to wonder why this grey slab draws so much attention.

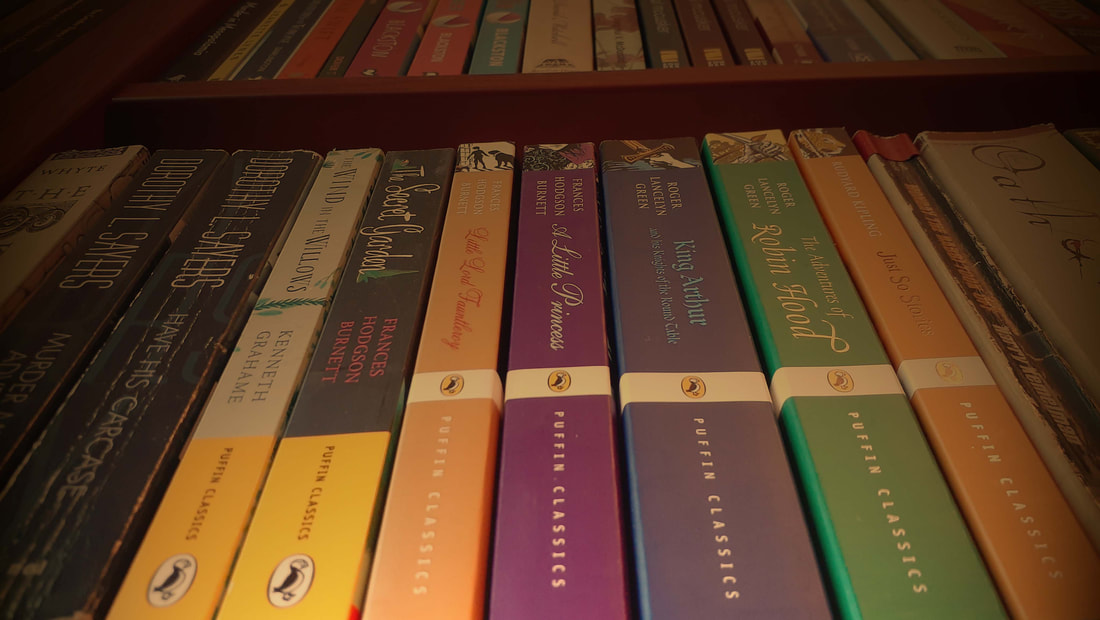

When I was in grade 7 we were studying ancient Egypt and for one of our assignments we had to write our name in hieroglyphs. We put so much effort into replicating those Egyptian symbols perfectly. It was fun because it felt like we were writing in a secret code. What we didn't know is that it was the Rosetta Stone that made this possible. For centuries no one knew how to read hieroglyphs. That knowledge had been forgotten. Egyptian written history, locked away in elaborate inscriptions on tombs and pottery shards, seemed forever lost to us. But that changed with Napoleon's military campaign in Egypt. In 1799 French soldiers were digging fortifications near the port city of Rosetta in the Nile Delta when they unearthed something rather heavy—a stone slab weighing roughly 1,680 lbs. They had accidentally discovered the Rosetta Stone. The world of ancient history can seem far away and even inaccessible. But it's closer than we think. Scholars were able to determine that the Rosetta Stone includes three copies of the same text, an ancient declaration of loyalty to Egypt's pharaoh. Since we already knew how to read the portion in Ancient Greek, suddenly we had the solution for deciphering hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone was the key that opened up to us the world of ancient Egypt. Novelist L. P. Hartley writes, "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." To me that's an exciting concept. It means the world of the past is alive and well, waiting to be uncovered. And there's always more out there to discover. This doesn't just apply to history. Just as the Rosetta Stone opens up the world of the past to us, fiction brings us into new worlds where we encounter both the familiar and the unexpected. Picking up a new a book is really a big moment. Worlds living just beyond our imaginations are all of a sudden flooded with light and life. When I think of the Rosetta Stone, I'm reminded how sometimes all it takes to break through into another world is finding the right key—or the right book. Do you remember opening up The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe for the first time, or better yet having one of your parents open the book up so that you could go to Narnia together? Do you remember what it felt like to visit that magical land of talking beavers and fauns, heroes and villains, mysterious forests and shining castles? It almost seems like a real place. There’s just something about the story that keeps drawing readers in.

Kids today still fall in love with Narnia, stumbling through the wardrobe with Lucy and her siblings, Peter, Susan, and Edmund. The four Pevensie children have an unforgettable adventure there and are crowned kings and queens at the end of the story by the great lion Aslan himself. But that’s only the first novel in The Chronicles of Narnia series. Other stories follow, characters come and go, and some characters change in surprising ways. Lucy’s sister Susan is someone who takes a turn later in life. When I was in grade five life was simpler. In math we learned about place value and had to memorize the difference between hundreds and hundredths. We read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe chapter by chapter and I got my mom to help me with the homework questions. We had lockers, but they didn’t have locks. My biggest worry was about improving my French pronunciation. And recess was all about four square. My classmates and I drew the lines in chalk every day—so often that the school eventually decided to paint permanent lines on the pavement. We thought that being the king of four square was the most important thing ever. But before we knew it four square was out. We had moved on to other things. Another year grounders was the big thing and another year it was chess. Some things we thought would last forever ended up being relatively short-lived in the grand scheme of things.

But that can be hard to foresee, especially when we’re young. Just consider fifth grader Jesse Aarons from the novel Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson. In Jesse’s little world success means being the fastest runner in his class. With that one goal in mind he trains hard for the whole summer, waking up first thing to go running. He comes back all sweaty from his morning runs just in time to milk Miss Bessie the cow. His sisters complain about him smelling bad after his runs, but that doesn’t bother Jesse too much. Better to be known as the runner than as the “crazy little kid that draws all the time.” Jesse Aarons, or Jess as people call him, returns to Lark Creek Elementary after the summer break expecting things to go his way. He imagines himself running across the finish line to the cheers and applause of his fans. His little sister May Belle will celebrate him as the winner. His classmates won’t pick on him for sketching all the time. And his dad will forget about work and spend time with him like the good old days. He’s going to make everyone so proud. After all, being the fastest kid in grade five is a pretty big deal. If you’ve travelled you know how exciting it can be. New sights and smells abound, from the wildlife to the night life, from the music to the food. There are so many unexpected wonders that come with experiencing another place, another culture. It’s almost like going to another world. But at some point you return to that familiar place, that place where you belong—home.

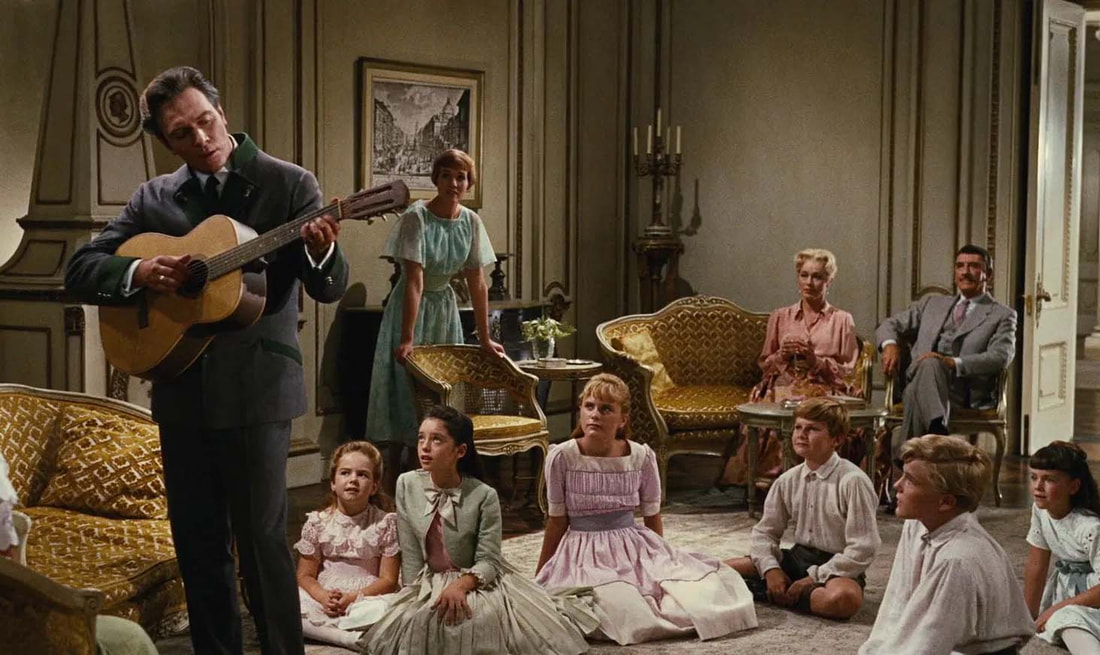

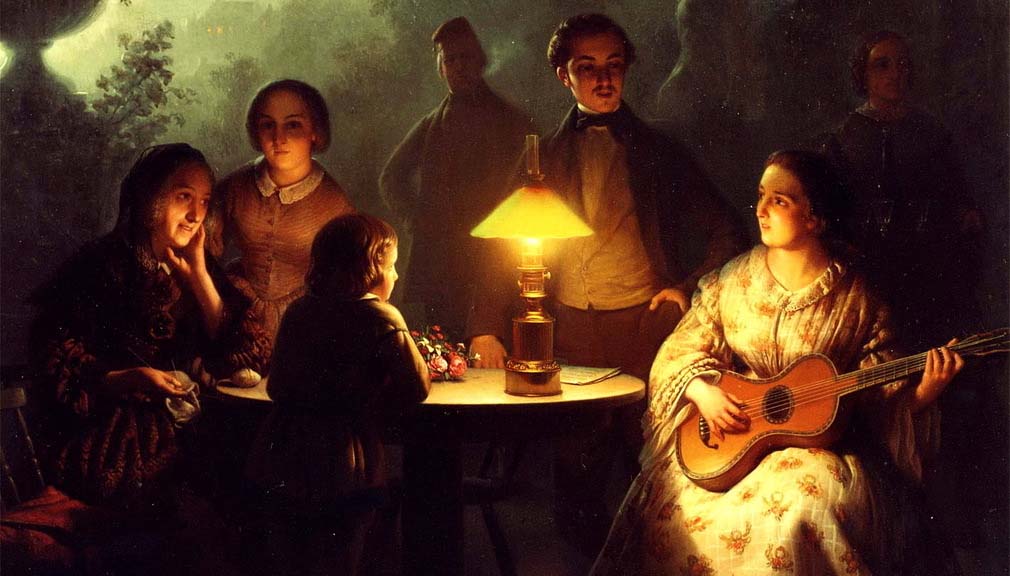

And perhaps all at once you realize something. Home feels different. You notice for the first time what makes your home so unique, the things you took for granted before. You realize how special home really is. The song "Edelweiss" appears in the Broadway musical The Sound of Music. The von Trapp Family Singers perform it on stage in front of a crowd of their fellow Austrians. It’s a song about a flower, yes, but it represents something more. It’s a celebration of home. Home in general and the homeland of Austria in particular. "Edelweiss" is a simple song, which is probably why I know it by heart. I always assumed it was a genuine Austrian folk song but it isn’t. It was composed for the 1959 musical. And yet this simple melody captures something deep and true. Having a good home is a blessing. It’s a place of comfort and safety. It’s somewhere to rest and relax, somewhere you know you can go to be refreshed, loved, and built up. There’s nowhere else like it. As The Sound of Music nears its conclusion, the von Trapps prepare to make their exit. They sing "Edelweiss" and a number of other songs to an admiring audience and receive a standing ovation. No one in the crowd suspects, however, what is about to happen next. The von Trapps are going to leave their beloved homeland, which has been taken over by the Nazis. Austria is no longer the country they know and love. It has become something else entirely, somewhere they are no longer welcome. The von Trapps make the painful decision to remain loyal to their real home, "the true Austria," which so many of their neighbours have forgotten. It’s often in leaving home that you realize how valuable home is. You see it for what it is, and how it suits you so well. Perhaps not all of us have a good place to call home. Not all of us know where we’ll find it. The song "Edelweiss" gives voice to a hope, a prayer almost, for wholeness and fulfillment. Its hope is that someday we will be restored and blessed once more with a place we all seek—a place to belong. We know what an audiobook is. Now you can hear professionals read books to you on your drive to work in the morning instead of having to read them yourself. You can listen to books while you do yard work or exercise at the gym instead of having to find the time where you can sit down to read in your favourite fireside armchair. Personally, I prefer fireside reading. Making time to read a book or read aloud to the family is so worthwhile. But if you're busy doing something on your own, sometimes an audiobook is the best option. They do have their drawbacks though. Some books don't work as well as audiobooks. Some voices are better suited for audiobooks than others. And then there's that bothersome concept of comprehension. How much do you remember from the audiobooks you've heard? For me there's a noticeable difference between the two. There's just no comparison to holding a physical book in your hands. But as it turns out, there's another option out there for hearing stories. It's called audio drama. Unlike audiobooks, today's audio dramas boast a full cast of actors, music, and sound effects. An audio drama is like a movie, but without the visuals. The movie plays in your mind instead of on a screen. The BBC has been adapting classic literature into audio drama on the radio for years. In the U.S., the long-running kids' show Adventures in Odyssey stands out as an example of original content. And there are many more great audio dramas out there waiting to be discovered.  Audio drama can captivate you for hours. I remember as a kid sitting in the living room drawing pictures or colouring or playing with LEGO, all the while listening through the audio dramas of all seven books in The Chronicles of Narnia. Whereas an audiobook sticks to a dry reading of the words on the page, an audio drama brings the story to life. It puts you right in the middle of the action. Unlike some audiobooks, audio drama is the farthest thing from being boring or bland. And yet it accomplishes it all with sound alone—no brightly flashing screen required. Whether you're looking for classics like Oliver Twist, Anne of Green Gables, and The Secret Garden, or the World War II era biographies of people like Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Corrie ten Boom, or even rare books that no one's ever heard of (see Lamplighter Theatre), audio drama has you covered. I think one of the reasons audio drama works so well is because it adapts the stories for the audio format. It's not simply a reading, but a dramatization. And it also allows sound designers to use the full range of tools at their disposal. These are stories which engage your imagination, stories you remember. Whatever genre you like or whatever age you are, there's something out there for you. I really can't recommend audio drama highly enough. “Where words fail, music speaks.” This quote is attributed to Hans Christian Andersen, the 19th century author of fairy tales such as “The Little Mermaid,” “The Ugly Duckling,” and “Thumbelina.” He’s saying that for all its precision and utility, language has its limits. There are times when words are not enough, when what seems inexpressible in words alone can only be expressed in song. That’s a very humbling thing for a writer to admit. You might think Andersen would privilege the written word above all else. But you don’t have to call yourself a musician to understand the truth in his statement. We know that we need music. I once heard a public talk about pseudoscience and mental health from a psychiatrist at university. His whole lecture was basically an attack on things like anti-stress colouring books, fidget spinners, and other products that people push while claiming they have mental health benefits, even if there is little evidence to back up their claims. Having thrown out nearly everything under the sun, the psychiatrist concluded that science does back the importance of at least two activities which contribute to our mental well-being. Exercise was one of them. The other was hearing music. (Personally, I would add a few things to that list, like reading, writing, community, and service, but then again I’m not an intensely skeptical psychiatrist, so what do I know?)  When I first watched The Fellowship of the Ring movie and heard the opening seven notes of the Shire theme, composed by Howard Shore, I was transported. It wasn’t the visual effects that brought me to director Peter Jackson’s vision of Middle-earth. It was that score. I was there with Sam as he lamented the departure of the elves into the far west, with Arwen and Frodo on the desperate gallop to escape the hooded Ringwraiths, and with the nine members of the Fellowship as they rested in the hallowed woodland of Lothlórien. The Lord of the Rings movies are indeed wonderful adaptations, though they don’t measure up to J.R.R. Tolkien’s books. And yet I’ve often thought that for all the changes the filmmakers made, it was worth it to have these films made if only because we got that musical score. We read about conflict all the time, whether we pick up a biography to learn the true story of Corrie ten Boom resisting the Nazis, or pore over a biology textbook to find out how white blood cells combat infection. Conflict seems to be an inescapable part of life. At a fundamental level stories are all about conflict. There's some challenge our characters face, some obstacle they need to overcome. We know what that's like. We experience conflict in our own lives, whether that's conflict with others or even within ourselves. We know what it's like to go through pain and heartache. Li-Young Lee's poem "The Gift" is about a boy who suffers a small yet familiar hardship. He gets a splinter in his hand. But thankfully for him, he has someone by his side to get him through. Here are the opening lines of the poem: To pull the metal splinter from my palm The love and care with which the father treats the boy stays with him. The poem goes on to describe the same boy as an adult, holding his wife's hand tenderly. He cares for her the way he's been taught, with gentleness and understanding.

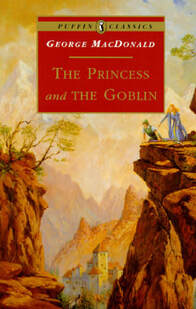

But let's think back to what exactly the father does. As he removes the splinter, the father tells the boy a story. Maybe this is only meant to be a distraction. Something to take the boy's mind off the pain. The poet might have included any number of things here to distract the boy, so why include a storytelling? Perhaps it points to the fact that just as stories are about conflict, they're also about resolution. Another word we could use for that is healing. Stories meet us where we are, in our conflict and pain, and show us where we can go. Heartache doesn't have to be the end of our story. There's reason to hope. The boy in the poem doesn't remember the specifics of the story. What he does remember is his father's calming voice. He remembers the bond of love between them. To tell a story is to share an experience with someone else. A storyteller creates a world out of thoughts and feelings and invites another person to enter in. Author and reader live the story together, sharing in the good times and the bad, experiencing hardship and relief. As readers we get the sense that someone else is with us, that someone else understands. The best stories reach out to us like a parent comforting a child. They let us know that whatever struggles we face, we don't have to face them alone. Have you ever had an epiphany? Maybe you suddenly realized that it really does hurt when you put your hand on the hotplate, or that leaning too far to one side in a canoe is likely to end in disaster. Or perhaps you've had an epiphany like Ebenezer Scrooge, who had a harrowing nightmare in which he was visited by a number of ghosts and woke up with not only a deep understanding of the meaning of Christmas but with a whole new lease on life. Epiphanies come in all shapes and sizes. What they have in common is this: an epiphany is a moment of clarity when we see things as they really are. Something clicks and we wonder how we didn’t see it before. The 2010 film Tangled presents us with a character very much in need of an epiphany. Based off the classic fairy tale Rapunzel, this version has the princess Rapunzel kidnapped as a young child and imprisoned in a tower by the old woman Gothel. Rapunzel grows up there, all the while totally unaware that she’s a princess. She believes Gothel is her mother. She trusts her captor wholeheartedly, never suspecting her sinister motives. Meanwhile Rapunzel's real parents, the king and queen, continue to mourn her disappearance. It’s only after a trip out of the tower that Rapunzel finally sees the light.  Which brings us to Flynn Rider. While Rapunzel is unaware of her origins and is largely oblivious to what goes on in the world beyond her tower, Flynn seems to understand the world pretty well and his place in it. Flynn’s escapades as a thief take him anywhere and everywhere, including over palace rooftops. When we first meet him at the beginning of the film it seems Flynn may have found his ticket to a life of ease and comfort. Rapunzel’s crown sits on a pedestal in the palace surrounded by armed guards. The crown is covered in jewels and has remained long untouched these many years. So naturally Flynn takes it for himself, with no concern about how the loss of the last remaining token of Rapunzel's memory might affect the king and queen. Nor does he bat an eye when he betrays his partners in crime, the Stabbington brothers, leaving them to the palace guards while he makes off with the crown. Flynn clearly prefers working alone. And better to betray others first before they have the chance to do it to you. A young princess finds herself in a kingdom beset by creeping shadows—monsters which lurk far underground. In the darkness below they tunnel endlessly, plotting to one day rise up and take over. Who from the kingdom will challenge this dark foe? Who is worthy to lead the forces of good to beat back the enemy once and for all? This is what fairy tales are made of. We know what's supposed to happen next. A prince will arise, seeking to win the heart of the princess. And what better way to do that than to fashion himself into a fearless, conquering hero who can do anything simply because he believes in himself? It makes perfect sense to our modern ears. As the great philosopher and poet of our age Miley Cyrus once said, “If you believe in yourself anything is possible.” (It’s impossible to find the source of this quote, but I'm sure we will eventually if only we believe in ourselves enough.) But while the prince is off on his own saving the day, one question remains. What's a princess to do in the meantime?  Perhaps Princess Irene can help us out with this question. In the children’s novel The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald, Princess Irene is an eight-year-old girl with a penchant for exploring. Her curiosity takes her to all kinds of exciting places, whether that’s getting lost on the rocky slopes of the nearby mountain as daylight begins to fade, or getting lost wandering the endless hallways and staircases of her father’s castle. Her poor nursemaid Lootie. She looks away for one moment and little Princess Irene is gone again, probably getting captured by goblins for all she knows. When Irene comes back one day with a tale about meeting her great-great-grandmother in the attic, Lootie will have none of it and notes that “princesses are in the habit of telling make-believes.” How should a princess act? Lootie has some pretty low expectations. If young princesses are indeed so prone to spreading lies then we can’t really expect better of them. No wonder the prince gets the responsibility of saving the day. Princess Irene, however, continues to defy expectations. She has some very different ideas for how a princess should behave. As she tells Lootie at one point, “Nurse, a princess must not break her word.” You see, Irene has standards. But it's also possible to take her statement the wrong way. Maybe she's saying that it’s perfectly all right for you vulgar peasants to engage in petty trickery and deceit, but as for us royals, we will not stoop to that level. Irene's standards show up again when she gets rather annoyed at Lootie for dismissing her strange story about talking to her great-great-grandmother. MacDonald writes, “Not to be believed does not at all agree with princesses: for a real princess cannot tell a lie.” Well, I guess that settles it. A true royal simply comes from better stock than the rest of us and is therefore naturally virtuous and morally superior. No wonder they’re granted the divine right to rule. No one else is qualified. |

David Raphael HilderJoin the conversation as we explore the best there is in fantasy, sci-fi, adventure, and of course, the classics Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|