|

Freedom is a great thing. It’s a fundamental building block of modern society. We take for granted our right to free speech, freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, and, for my American friends, freedom to organize a militia and revolt against the imperial overlords at the slightest hint of taxation without representation. The right to elect representatives to decide the right tax for loose leaf chamomile tea shall not be infringed. The world we live in today really is a new world. It’s less hierarchical and more socially mobile than the old world. Despite starting out in poverty, people like J.K. Rowling can make millions of dollars a year writing stories about little wizards going off to boarding school. Meanwhile, the spread of technology has democratized knowledge, giving us access to all the true crime podcasts and cat videos we want. We like our freedoms, and we’d rather nobody put restrictions on them.  If we don’t have freedom, we fight for it. The 1992 animated classic Aladdin includes a number of characters searching for freedom. They want to leave the old world behind and find their way into a new world. The princess Jasmine, for instance, feels trapped by rules and palace walls. It turns out being a royal isn’t all just wealth, privilege, and pet tigers who strike fear in the hearts of your enemies. It brings with it certain restrictions. Jasmine’s marriage prospects are limited to wealthy princes who happen to impress her father, the sultan. Commoners are excluded from the running. Though, it’s not like Jasmine has many opportunities for meeting commoners. She doesn’t even get to leave the house. In an unmistakeably symbolic moment, Jasmine flings open the door to a bird cage and lets loose a flock of doves. She watches them with longing as they soar up into the atmosphere. Here’s to hoping the doves had long, fulfilling lives and didn’t end up being served on a plate with a side of mashed potatoes the moment after they were freed. Aladdin is at the opposite end of society. As Agrabah’s most successful thief, Aladdin seems like he’s doing pretty well. He easily weaves his way through crowds and over rooftops, outwitting the authorities at every turn. With a smile on his face he sends his trusted monkey Abu to distract the merchants while he gets the goods. Breaking the rules all day long, you’d think Aladdin would feel like a free man. He can get anything for himself at no cost. Plus, he has that cool little fez he wears. What more could he want? Yet Aladdin feels just as trapped as Jasmine. Prince Achmed, one of Jasmine’s many suitors, calls Aladdin “a worthless street rat,” saying, “You were born a street rat, you'll die a street rat, and only your fleas will mourn you.” That’s a little unfair. I’m sure the rodents of Agrabah would show their solidarity as well. But maybe that’s a small consolation when you’re constantly on the run, with guards pointing their swords at you on every corner.

Comments

Adventure is an exciting word. We think of journeys across windswept seas to find buried treasure and battles with gnarled monsters from subterranean depths. Adventure is about excitement and new experiences. It’s about entering boldly into the unknown. In my last post I wrote about the need to say yes to the call to adventure. I said that it’s only when we enter into the unfamiliar and uncomfortable that we make room for growth. But sometimes we’re led in the wrong direction. There are times when adventure can bring us to a dark place where the only way out is to find the way back. As C.S. Lewis says, sometimes progress doesn’t mean going forward, but rather turning right around and going in the opposite direction. Adventurers should take note. Openness gets you started on the journey, but discernment tells you which way you’re going. If an adventurer isn’t careful they might be swept away by their circumstances. That’s what happens in the 2001 animated film Spirited Away, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. It begins with a journey. The girl named Chihiro is moving to a new home with her parents. But the story really gets going when something happens on the car ride. One moment they’re cruising through the suburbs and the next they’re on a dirt road surrounded by forest. Chihiro doesn’t like the looks of the swaying trees, but her father welcomes the situation and plows eagerly ahead. He claims he’s not worried because he has four-wheel drive. And this is where our characters start to go wrong. They don’t understand that they’ve been sidetracked from their destination and brought to the doorstep of another world. Chihiro’s father sees himself as capable of conquering everything he sees. He hasn’t learned yet that not every situation can be approached boldly with an impatient stride and an upright posture. Sometimes having your knees knocking together and your head stooped humbly is the appropriate response. And sometimes it’s better to keep your footing and run the other way.  Chihiro and her parents find themselves in another world, a world of spirits where Japanese mythology comes to life. They pass by a shrine on the road but don’t pay too much attention. Chihiro is the only one of the three who gives it a second thought. Most of us don’t expect to encounter a whole magical world around the next corner. And even if we did, these days the word magical has mainly positive connotations. A magical day is a great day. Disneyland is called the Magic Kingdom. Chihiro’s father even says that the town they come across looks like an abandoned theme park. To us a little magic sounds like entertainment. It’s a welcome escape from the modern inconveniences of commuter traffic, hackers, and the threat of nuclear war. But people haven’t always thought that way. In the past magic had real power over people. It was a world with a spirit behind every tree and at the bottom of every well. Our ancestors had greater respect, you might even say fear, of magical powers. While I'm not advocating a return to a world held in bondage by those superstitions, I think we can still remember to have a healthy respect for what we don’t fully understand. And we should watch out the moment we find ourselves being pulled towards whatever promises to be the primrose path.

Life is a series of choices. Some are big choices, like who to get married to. Others seem small, like what to have for breakfast. Porridge? Or perhaps an egg-free tofu omelette. All these choices, big and small, have led you to this moment. They’ve had on impact on your education, career, health, and relationships. One choice leads to opportunities for more choices and pretty soon you can look back on your life as a long string of decisions. This is your story, almost as if you were a character in a book. And it all starts somewhere. But before each stage of your story can really begin, you must make an important choice. It's the choice of how to respond to what Joseph Campbell entitles "the call to adventure." In Campbell’s description of the hero’s journey, the call to adventure is where everything takes off. Our main character receives a revelation. Perhaps they discover that a whole other world exists, an unknown world "of both treasure and danger." It’s an exciting place, but also unpredictable. And so like Neo in The Matrix, they come to a crossroads. The blue pill or the red pill. It is the choice of whether to continue being comfortable with what they know, or to take a chance and step out into the unknown.

Why would anyone ever leave what they know in order to be uncomfortable? That doesn’t sound very relaxing. Or safe. And more importantly, what would the neighbours think? Bilbo Baggins deals with those exact concerns in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. The Bagginses are seen as "very respectable" in large part "because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected." But when Gandalf and his throng of dwarves show up on the doorstep for an evening of telling tales about the battles and treasures of faraway lands, something awakens inside Bilbo’s heart. He realizes there’s more to life than tea, buttered scones, and seed-cakes at Bag End. There’s a whole other world out there, and it starts at the little road just outside his front door.

Fantasy worlds are where dreams come true, especially when it comes to Disney-style fairy tales. Sleeping Beauty, for example, is a princess expecting a handsome prince to rescue her, and that’s exactly what happens. In the end everybody gets what they wanted all along. That was 1950s Disney. But then in 2001 DreamWorks Animation came along with their little film Shrek and shattered what we think of as the traditional fairy tale.

Inspired by the picture book by William Steig, the film Shrek starts with the reading of a story about a princess locked in a tower being guarded by a ferocious dragon, awaiting true love’s first kiss. At that moment Shrek laughs and says, “Like that’s ever going to happen!” He rips off a page from the storybook and presumably uses it as toilet paper. You’d be hard-pressed to come up with a more irreverent opening if you tried. And with that, Walt Disney’s work gets flushed down the drain.

Over and over the film reminds us of our fairy tale expectations, only to dash them to pieces in front of our eyes. We watch as Geppetto sells Pinocchio for “twenty pieces of silver” and Peter Pan betrays Tinkerbell. Lord Farquaad wants to marry a princess, not out of love but to make himself king. When the Magic Mirror runs through three eligible candidates, describing Cinderella as “a mentally abused shut-in,” Farquaad can’t decide on which lucky lady to make his bride and seems to choose Fiona only by random selection. Being too cowardly to free her himself, Farquaad sends off Shrek the ogre to do his dirty work.

Fiction has given us some memorable bad guys over the years. Where would Harry Potter be without Voldemort, or Sherlock Holmes without Professor Moriarty? Villains fascinate and challenge us. And they’re usually ten steps ahead of our heroes. The sci-fi villain has a high-tech surveillance system and the fantasy villain has a crystal ball. Somehow or other they find out what’s going on and plan accordingly. Sometimes a villain can come across as a mastermind. The Dark Lord Sauron, from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, is a real schemer. As the fires burn in the depths of Mount Doom and the billowing shadow stretches across the sky from the land of Mordor, Sauron broods over his plans. He has but one goal. His whole will is bent on seeking his lost treasure: the One Ring to rule them all. With it he can subdue the world. If the Ring is destroyed, so is he. Conveniently, Sauron is in possession of Mount Doom, the only place where the Ring could be destroyed. And yet this so-called mastermind fails to take a few simple measures to protect himself, such as sealing the giant door on the side of the mountain or placing a few monstrous creatures to stand guard. How does Sauron make such a fantastic blunder? And how is he distracted by a puny army knocking at his front gate? Let’s find out.

Tolkien’s book The Silmarillion covers the history of Middle-earth before The Lord of Rings, including Sauron’s origins. It turns out there was another dark lord before Sauron named Melkor, a heavenly being who sought to corrupt and wage war against creation, especially elves and humans. When his malice was revealed, Melkor came to be called Morgoth, a name you’ll remember if you, like me, have watched The Fellowship of the Ring movie more times than you care to admit. After Gandalf falls to a fiery Balrog in the Mines of Moria, Legolas calls the creature "a Balrog of Morgoth." A servant corrupted by the first dark lord. The new dark lord, Sauron, was also a servant of Morgoth at one time.

Some people are just amazing. Einstein and Shakespeare, for instance, stand out as exceptional. Joan of Arc led the armies of France as a teenager. In the film Amadeus, Mozart seems to compose concertos and symphonies with little to no effort, while his rival composer Salieri painstakingly works to produce material which can never measure up. It appears some people are chosen for great things, gifted with special abilities, while others are not. And that’s reflected in the stories we tell.

Let’s take a look at A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. In this story, boy-genius Charles Wallace Murry speaks with a vocabulary well-beyond his years, probably on account of his reading the dictionary for fun, and at five years old he quickly grasps the concept of travel through time and space. But he’s more than just your average child prodigy. As his mother says, "Charles Wallace is what he is. Different. New." You might say, unique. The boy knows things about people without being told. He can feel around in other people’s minds, and he can usually tell whether a stranger is friendly or sinister. His gifts go far beyond what you would expect.

With everything going for him, you’d think Charles Wallace would be the story’s main character. Wouldn’t you as a reader like to spend some time in the head of a genius and see things from his perspective? But instead L’Engle chooses to present the book to us through the eyes of Meg, Charles Wallace’s older sister. Meg is best known for not being able to control her temper. She gets in plenty of trouble at school and is stubbornly protective of her brother. She certainly doesn’t feel gifted. Rather, she believes she’s "doing everything wrong." Meg can’t seem to keep from lashing out, and the fact that people are gossiping about her missing father doesn’t help matters.

Many fantasy stories focus on a journey, whether it’s the quest of King Arthur’s knights to find the Holy Grail or the long homeward journey of Odysseus after the Trojan War. Those chosen to come along on such quests are often selected for their loyalty. They believe in the cause. They will try to persevere until the end. These companions are faithful to the quest, but they may have no idea how to reach their destination. Like the crew of a ship, they may not know the exact path to take or which stops to make along the way. They need a captain, a leader, to guide them. But leaders can have different tactics to get the job done. Michael Scott, played by the always hilarious Steve Carell on the show The Office, has a unique perspective. While contemplating how he wants his employees to view him, Michael says, “Would I rather be feared or loved? Easy, both. I want people to be afraid of how much they love me.” The line is a reference to the 16th century political thinker Machiavelli, who came to the conclusion that “it is much safer to be feared than loved.” Rule by fear is self-explanatory. It keeps people in line. It’s practical and efficient. Rule by love, on the other hand, sounds like a contradiction. How does one even do that?

The characters of How to Train Your Dragon have a possible solution. (Spoilers ahead.) The film, loosely based on the book series by Cressida Cowell, follows a boy named Hiccup, a member of a Viking village which gets raided by dragons on a frequent basis. Needless to say, they're not too fond of dragons burning down their homes and stealing their livestock. At first Hiccup is all on board for killing the dragons, until he encounters one face to face. He shoots down a Night Fury, the rarest of all dragons, and finds it trapped and injured. He approaches it with a knife as it lies helpless before him. Killing the beast would make him a hero in his village. But he just can’t bring himself to do it. And so, in a moment of mercy, Hiccup uses his knife to cut away at the dragon’s bonds and give the creature its freedom.

When you hear the word hero, who do you picture? If you’re a Marvel fan you might think of Iron Man, Black Widow or Captain America. We look up to heroes like these because they can do what we can’t. They use their godlike powers to fight against evil, saving the world from one earthshaking supervillain after another. Whether our heroes have the shining idealism of Superman or the dark, gritty realism of Batman, they all use their power for good.

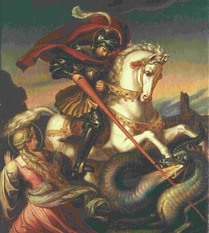

Power seems to be a precondition. If you don’t have power, how can you do anything? And the fantasy genre is famous for giving us powerful, larger-than-life characters. Fearless warriors clash against monsters from the depths of hell. Cunning wizards bring down the skies in magical duels to the death. Mighty knights battle against fierce, fire-breathing dragons. The people of medieval times were no strangers to such tales. One of their great heroes, Saint George, was famous for reportedly slaying a dragon.

But does a hero need to be powerful? While fantasy does give us some of the most powerful characters you’ll find anywhere, it also has the curious tendency of presenting us with heroes who seem weak and totally inexperienced. Think of young Charlie stepping into Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory or Bilbo Baggins being swept from his little hobbit hole on an adventure into a world of goblins and even a dragon. In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy is followed by a band of blundering misfits, including a brainless Scarecrow and a lion who’s afraid of his own shadow. These are not the heroes of ancient epic. At first glance they don’t look like heroes at all.

Christmas is fast approaching and the mad rush to purchase last-minute gifts is in full swing. The season brings with it plenty of sweets, colourful lights, and crowded department stores. For those of you in more northern climes, chances are you’ve been trekking through the snow and ice to do your holiday errands. And finally, the big moment will arrive. You give the gifts, Santa Claus gets the credit, and everybody sits down to eat too much Christmas ham, or your poultry of choice. But believe it or not, that isn’t the only way to celebrate Christmas. They do it a little differently, for example, in Narnia. When we first encounter Narnia in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe it looks like a snow-laden wonderland of sorts. It’s kind of magical, really. But as Mr. Tumnus the faun soon reveals, there is apparently something sinister behind the beautiful quiet of the falling snowflakes. He tells Lucy that the White Witch "has got all Narnia under her thumb. It’s she that makes it always winter. Always winter and never Christmas; think of that!" Sounds horrible. But think of all the time you’d save not having to scour the aisles for stocking stuffers.

If you remember the story, the Narnians do get to have Christmas eventually. As Peter, Susan, and Lucy Pevensie follow Mr. and Mrs. Beaver through the snow, hoping to escape from the White Witch, they hear the sound of an approaching sledge and its jingling bells. Who else could it be but the witch herself, hoping to catch them before they reach Aslan’s army? But it isn’t. As C.S. Lewis describes the scene, "on the sledge sat a person everyone knew the moment they set eyes on him. He was a huge man in a bright red robe (bright as hollyberries) with a hood that had fur inside it and a great white beard that fell like a foamy waterfall over his chest." Father Christmas himself.

Have you noticed something? Fantasy has gone mainstream. What was once a genre only acceptable for a select group of people on the fringes—the eccentrics, the nerds, the gamers, the binge-readers, etc.—is now all of a sudden widely popular. People are glued to their screens watching Game of Thrones, Supernatural, and Once Upon a Time. Amazon is developing a new Lord of the Rings series and Netflix has taken the reins of The Chronicles of Narnia. Meanwhile, this year the Harry Potter books passed the 500 million mark in copies sold.

Fantasy is no longer one of literature’s best kept secrets. Maybe we’ve come to realize that these kinds of stories aren’t just for children. Adults can enjoy them too. I grew up reading fantasy books. Like you, perhaps, I was guided by the wisdom of Gandalf and heeded the warnings of Galadriel. I followed along with Lucy as she stepped through the wardrobe into Narnia and with Wendy as she sailed into Neverland. These stories have stayed with me. And I’ve only gone looking for more such adventures since then.

Why do we love fantasy? What drives us to come back to it again and again? It might help to think about what we mean by the word fantasy. In everyday conversation the word can have an unhealthy connotation. It denotes something we think about continually but which is very unlikely to happen. Fantasizing denies what’s real. And it can cause real-world problems. For example, you might fantasize about gambling your way into financial success, and then lose everything. Or your co-worker might be convinced that, despite all evidence to the contrary, you're looking to take over their job. Fantasizing can lead us astray when we refuse to believe our eyes and ears. |

David Raphael HilderJoin the conversation as we explore the best there is in fantasy, sci-fi, adventure, and of course, the classics Archives

December 2020

Categories

All

|